Meg and Megg and the appropriation of childhood

This is a post about the appropriation of childhood I see in Simon Hanselman’s comic Megg and Mogg. Before I get into it, I want to set a few parameters. First, I am discussing the comic only in relation to the appropriation issue. Yes, there’s lots of other interesting stuff but not here not now. Second, my own opinion of Megg and Mogg is irrelevant and so is yours. Personal taste is neither an indicator nor defense for appropriation. Third, I have no idea whether Simon Hanselman is conscious of his appropriation behaviours or not, or what his motivations are either way. It doesn’t matter.

And finally, the footnotes are helpful!

I’ve long felt disquiet about Simon Hanselman and his1 Megg and Mogg comic. This has nothing to do with its ‘adult themes’ but rather the idea of a man intruding on a space originally meant for young people; the cultural appropriation of childhood.2

By way of context - Simon Hanselman makes a popular, explicit grown-up comic called Megg and Mogg. Its main characters are a witch called Megg, a cat called Mogg and an owl called Owl. They live in a squalid flat and struggle with drug use, sex, violence, depression, poverty, and their feelings about each other.

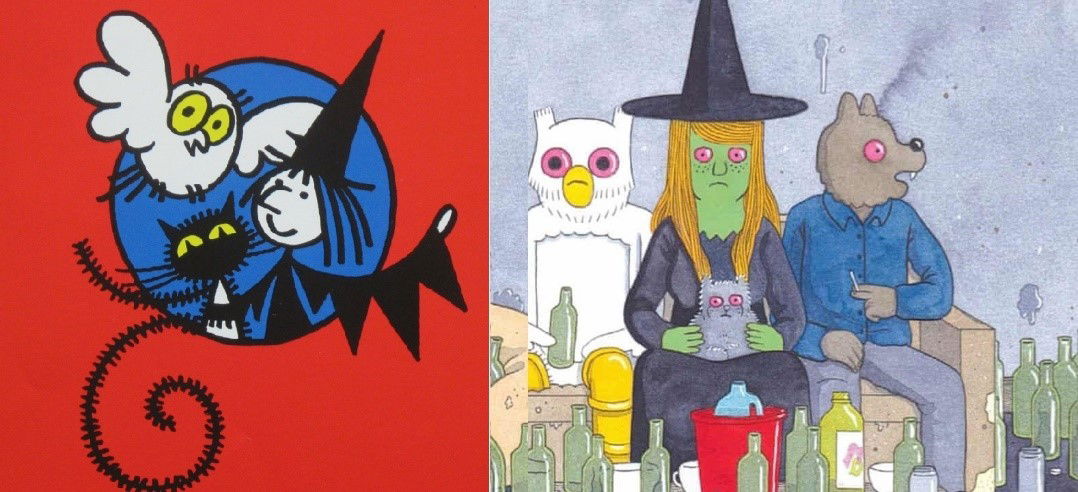

Hanselman’s characters reference those from a popular series of children’s picture books called Meg and Mog. In these Meg is also a witch, Mog is also a cat and there is also an owl also called Owl. They’re all friends and have adventures based on Meg’s fascinating and powerful spells. The books are written by Helen Nicoll, illustrated by Jan Pieńkowski and appeared around forty years before Megg and Mogg the comic.

Meg, Mog and Owl, and Megg, Mogg and Owl

I am not prissy or squeamish or frigid or PC gone mad but as I said, the Meg and Mog and Megg and Mogg thing does not sit easy. As I also said it’s because of the appropriation. Simon Hanselman takes from the culture of childhood - because he can – and uses what he takes for personal gain.

Appropriation-related discourse is everywhere. It’s symptomatic of a growing and righteous fury about the ways historic cultural and economic structures have enabled the plundering of treasures – ideas, artefacts, values, traditions, history, language – for the crass and commercial benefit of (mostly) wealthy white men and their insidious interests and empires. Most of the current public discussion is about cultural appropriation but there’s also some related to disability, mental health and intellectual property.3

Childhood appropriation is comparable and I really did think I’d find some serious reference to Hanselman’s flagrant raiding. Instead however I found only unquestioned admiration; the use of Meg and Mog described as ‘wonderfully sacrilegious’, a ‘stoner reimagining’ and ‘dark parody’ of… ‘a beloved children’s classic’.

It is none of these things (I will explain why later). It is appropriation. I know this because appropriation has criteria, and Simon Hanselman and Megg and Mogg meet all of them. Here they are and here is how -

A precious thing is taken

Appropriation involves taking something that’s (in some way) tangible and is understood as coming from, and having value, somewhere else. The social meanings and signifiers of appropriated objects are as visible as the objects themselves.4

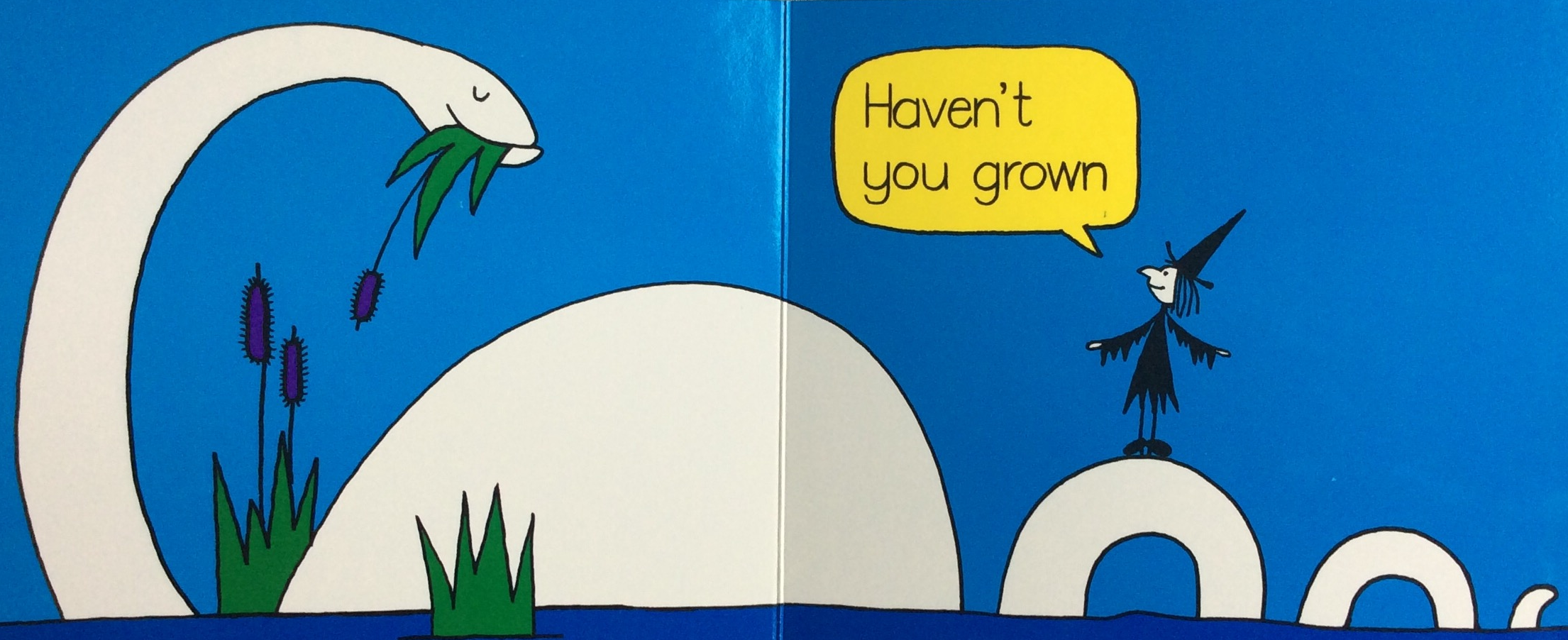

Picture books signify ‘childhood’5 as do the imagined worlds, fantasy creatures and exciting adventures within many of them. Stories are generally seen as nurturing spaces within which children can safely develop imagination, curiosity, wonder and a sense of adventure.

The Meg and Mog titles exemplify the above. They are about magic creatures and magic deeds within a magic world, made safe and accessible through humor, bright colours, clear language, simple symbolical drawing and an enduring theme of friendship. They’ve been in print since 1972 and are beloved. People remember them happily as a part of their childhood and buy them for their own children.

Picture book form + fantasy content + individual memories mean that Meg and Mog = ‘childhood’. Simon Hanselman has taken something real, valued and widely understood as belonging somewhere else.

The taken thing now kind of means something different

Although an object’s inherent social meaning remains wherever it is taken, its contextual meaning changes. These two realities jar and offend but appropriators behave as if this is no big deal.

Simon Hanselman’s comic world is one of extreme adulthood6 and to exist there Meg and Mog and Owl must be different (even though they remain the same). Meg is still a witch with a black hat but loses her determination, agency, joy and humorous stick figure appearance. As Megg she is instead depressed, suicidal, drug addicted and has the stacked three-dimensional body of an adult woman. Mogg and Owl are similarly grown-up.

The Meg/Megg contrast is intensified by the child/adult contexts to which they correspond. This works to the comic's advantage. Megg’s defining debauchery, desperation and despair are so much worse when compared with the wonder and clean living of her namesake. There's also an implied distain for children’s literature that adds to Megg and Mogg's nihilistic reputation.

Meg and Mog clearly influences Simon Hanselman’s work but he downplays this. Minimizing the original value and meaning of something, by whoever’s taken it, is another appropriation indicator. The idea is that the change in context is so extreme only a fool would think any primary definition is relevant and thus any whiff of disrespect or dependence is neutralized. Hanselman says, “Sometimes I forget that those old kid's books even exist. And there really are zero similarities beyond the names and the ‘classic grouping’ of a witch and her familiars”.

The thing is never theirs

Another key feature of appropriation is the taking of something that does not belong to you because it’s from a group you are outside of. Meg and Mog belongs to children and Simon Hanselman's social identity or group is adult man. He can never be childhood and childhood can never be him.

Hanselman’s outsider status also explains why Megg and Mogg can not be parody7 reimagining8 or sacrilege.9 Although not identical, these activities all require those doing them to be members of the group or culture that ‘owns’ them. If they’re not it’s at best awkward, at worst offensive and sometimes it’s appropriation.

Whoever took the thing is in charge

Appropriators are outsiders and they are powerful outsiders. They always belong to a group that has an entrenched dominance over than the one they’re taking from. All adults have an inherent authority over children. Children need adults for love, protection, education, food and shelter. This dependence is a (necessary) feature of childhood but means adults are always more powerful than children. Simon Hanselman is an adult.

Despite the existence of the thing, it’s all their own work

Minimizing origins happens not just in relation to what an item is or means or the cultural context it comes from. It’s also about failure to acknowledge any specific creators or connections. At no time does Simon Hanselman give any credit to Helen Nicoll and Jan Pieńkowski for developing the characters he’s appropriated. In fact he explicitly tries to cut them out,

“I do worry about the legal side of it sometimes. Are those extra ‘G’s enough?... Somebody wrote me up into that wiki entry about eight months ago, dubbed the comic a ‘pastiche’. I edited it out of the entry, paranoid it would ruin my book deal negotiations with a cease-and-desist order. I ended up signing a deal and they don't seem to think it's an issue. I guess as long as the title on the cover isn't Megg, Mogg and Owl there shouldn't be a problem”.

So Hanselman sees ‘acknowledgement’ not as deserved, appropriate or ethical but as ‘a problem’, something that threatens his ability to reap the financial and reputational rewards of his comic.

Hanselman also avoids the idea that he's actively ‘taken' from others. He says, “I started drawing Megg & Mogg when I moved to the U.K. in the same area that Jan Pienkowski lived and worked on his Meg and Mog. I had no idea at the time that he had lived there. It was a strange coincidence. It was some kind of magic in the air”.

Those words ‘coincidence’ and ‘strange magic’ imply an environment beyond the bounds of everyday life and control. It feels like Hanselman thinks the universe bestowed Meg and Mog upon him, that he was merely an empty vessel ready to receive some kind of cosmic comic grace. Absolving yourself of responsibility in this way is another appropriation signal.

Simon Hanselman and Megg and Mogg appropriate Meg and Mog and through this, childhood. Like I said, the situation meets all the criteria.

'Meg's Eggs' has a lake monster in it

Up until now I have tried to provide an intellectual analysis, to rationally link Hanselman’s actions to the concept of appropriation via definitions and examples. I’m going to end however with some personal, honest and quite grumpy thoughts –

It is the adult – child power dynamic that allows for adults to do heinous things to children. I am not suggesting that Simon Hanselman’s actions are anything like this. At a conceptual level however, the vaguest whiff of the idea of an adult man entering children’s space uninvited - regardless of their purpose - makes me uncomfortable.

Hanselman’s refusal to give Helen Nicoll and Jan Pieńkowski any credit is selfish, unethical and just shitty. And I hate how no one ever notices or calls him out, instead he's praised for his 'clever subversion'. Self-serving capitalism anyone?

That thing he says about there being no resemblance between Meg and Mog and Megg and Mogg other than their names and species and that he forgets Meg and Mog even exists? I immediately thought of Prince Harry at that party in his Nazi costume, “You know, sometimes I forget the Third Reich ever happened. Beyond this Swastika and uniform there’s really no connection”.

My own Meg and Mog fandom is compromised by Megg and Mogg. As is my admiration for Simon Hanselman's drawing style and relentlessness.

A huge number of people I know like or love Simon Hanselman’s comics. They buy the books and wear the t-shirts and post panels and pages on their Instagram feeds. None of this means anything in relation to appropriation-proper but it does make the act of talking about it quite difficult. But I am a punk and a feminist and I have a moral obligation to call out problematic behaviours even when it’s hard and exhausting to do so. So I am.

Megg and Mogg is childhood appropriation. Give no fucks, carry on reading and loving the comic, whatever. But let’s call it what it is.

[1]Simon Hanselman says he identifies as a ‘straight male’.

[2]In this post child/children/childhood refers to westernised only.

[3]Try searching Vera Rubin or Chien-Shiung Wu or Katherine Johnson or Trotula of Salerno or Big Mama Thornton or Margaret Keane or Una Mae Carlisle or Katinka Hosszu or Marion Mahony or Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven…

[4]E.g. feathered headdresses worn at Coachella are part of Native American culture and we ‘know’ this.

[5]They have been for a long long long time. Written by John Amos Comenius, Orbis Sensualium Pictus is the first known picture book. It was published in 1658 and was made for children.

[6]In one story, as a birthday surprise, Mogg and a werewolf pal attempt to rape Owl, while Megg watches.

[7]To 'parody' is to ridicule or criticize something through imitation. To work it must be close in form to the source subject which in turn has to be extremely familiar to the audience, i.e. from the same group. Otherwise it’s just stereotyping and mockery. In addition many interviewers talk about being unfamiliar with Meg and Mog the picture book, so they can’t be reading Megg and Mogg as parody.

[8]A well-known example of ‘reimagining’ is that thing where a group of close female friends - if they want to - can lovingly call each other ‘bitch’. In this context the word’s not offensive, it’s ‘reimagined’ as a term of endearment. Those outside of the group cannot partake of this and it’s awkward and offensive if they assume they can.

[9]‘Sacrilege’ is irreverence to sacred objects and acts within your own group (originally the term was even more context-specific, applying only to the act within the Catholic church). When you do the same thing within a group not your own, it’s not ‘sacrilege’ but intolerance / discrimination / hatred.

Simon Hanselman quotes and references from -

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2016/apr/14/simon-hanselmann-interview-megg-mogg-and-owl

https://www.avclub.com/megahex-s-simon-hanselmann-on-comics-cross-dressing-a-1798272682

https://www.tcj.com/disgusting-creatures-the-simon-hanselmann-interview/

https://issuu.com/forgeartmag/docs/issuu22/s/122384

https://tvtropes.org/pmwiki/pmwiki.php/ComicBook/MeggMoggAndOwl