Objects, Victorians and unreadable books

I was watching one of those strangely soothing home tidying and sorting shows. The very helpful and determined women hosts were very much into sorting their client’s books by colour, making blocky rainbows across the shelves. My instinctive reaction was one of indignance, kind of a ‘how dare they reduce the thoughts, stories, information of the world to home décor?!’ My second reactions was, ‘wtf Indira. Get over yourself. Besides you’ve always been interested in the book as an object, remember?’1

And oh yeah that’s right. I even once even wrote a conference paper about it. I am going to adapt part of this for you right here right now. I still think it’s an interesting topic, plus I am fully into recycling old ideas and obsessions. What else is a blog for?

The usual way to frame books as objects relates to the influence the physicality of print and paper has on the experience of reading, often looking at how it’s different to reading in a digital format (please note the word ‘different’. Analogue and digital have their own affordances but neither is inherently superior to the other). This incorporates things like weight, smell, size, the picture on the cover, the satisfying crack of a spine, scribbles in the margins, the way the pages are chronological and lead you through a story.2 That kind of thing. It’s about the book as a container for text (of whatever type) and maintains reading as its fundamental use. And yep, can’t argue and don’t want to.

But! It is quite exciting (and a bit delightfully sacrilegious) to disregard this and instead look at a book as an object proper; to think about the other things a book might be.

Here are some interesting people’s interesting ideas about this interesting thing -

Elizabeth Mayo and the Object Lesson

The Object Lesson was part of the pedagogy of Swiss educator Johann Pestalozzi (1746 – 1827). He believed children learned best through direct interaction with their environment and that language and the faculties of abstraction would develop from this. His ideas caught on and were adapted in a bunch of places by a bunch of people including British teacher Elizabeth Mayo.4

Elizabeth Mayo (1793 – 1865) was the first person to ever write a textbook, i.e. a practical book with things to do in a classroom rather than an educational philosophy tract.3 It was a book instructing teachers in the undertaking of an object lesson and contained one hundred objects with questions designed to guide children in their thinking and describing. It was a best seller, published in multiple editions and languages between 1830 and 1865. Some full text versions are here.

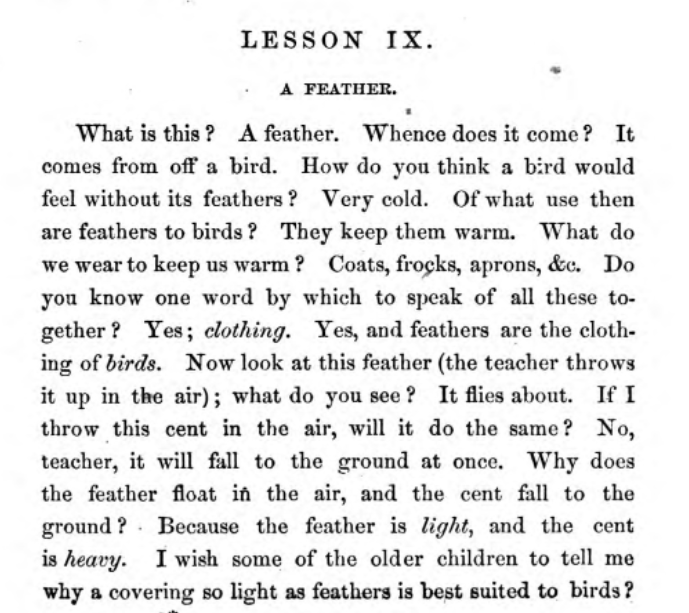

The book worked like this - the teacher would show the object (or a picture of the object) then ask a series of questions related to its appearance, tactile qualities, purpose, history, relationships to other objects, names of its parts etc. Here’s a feather example:

As you may have guessed there’s an object lesson about books and it could not be less concerned with exploring them as something to read. Instead the focus is on the sharpness of the edges of the cover, the typeface used, the width of the margins, and what kind of stitching holds it all together. This isn’t surprising because at the time book learning was viewed as the antithesis of the object lesson; ineffective and even dangerous in its untethered ideas, generalisations and lack of sensory relatability. This was a period where books were often seen as inherently bad for children, inhibiting both their physical and mental development. Parents, teachers and publishers went out of their way to teach reading via other means. True story.

How to Do Things with Books in Victorian Britain by Leah Price

How to Do Things with Books in Victorian Britain is written by Harvard English Professor Leah Price. It is thoroughly researched and deftly argues that reading is not necessarily the most important thing people do with books.

Price concentrates on the 19th century when due to technology, books truly became a mass medium. This is often presented as the beginnings of a literacy explosion and the advent of widespread education and bettering oneself and the opening up of the world and minds and the spread of democracy and that kind of thing. Price posits that it was not all like this, that advances in printing didn’t automatically lead to more people reading great literature. She says it also led for example, to the rise of junk mail and annoying religious manifestos, stuff to be avoided. So for many paper was valued less as a reading medium and more for what you could do with it. Even the crappiest book retains worth as paper for lining pie tins, making dress patterns, curling hair etc.

This central thesis contains within it, explorations of class, capitalism, elitism, industrialisation and other thought-provoking stuff. The book is dense and convincing although the writing won’t be everyone’s cup of tea,

Mental actions prove harder to track than manual gestures, human traces that are not intentional, let alone textual, let alone literary. From evidence of reading to nonevidence of reading to evidence of nonreading: those bodily acts that both accompany and replace reading, whether licking a page or turning down a corner, should provide historians of the book with more than a consolation prize. Like the dog that didn’t bark in the night, the book with uncut pages constitutes evidence too.

But I like it.

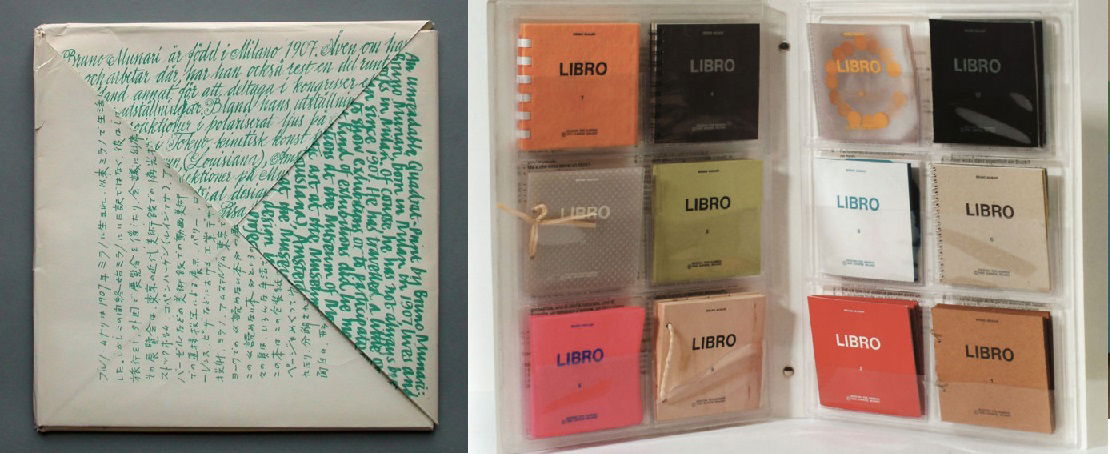

Bruno Munari and Libri Illeggibili

Bruno Munari (1907 – 1998) was a ‘proper’ children’s book illustrator. He was great at this, creating gorgeous, original narratives through surface marks and die-cut images. He understood and championed books as receptacles for stories.

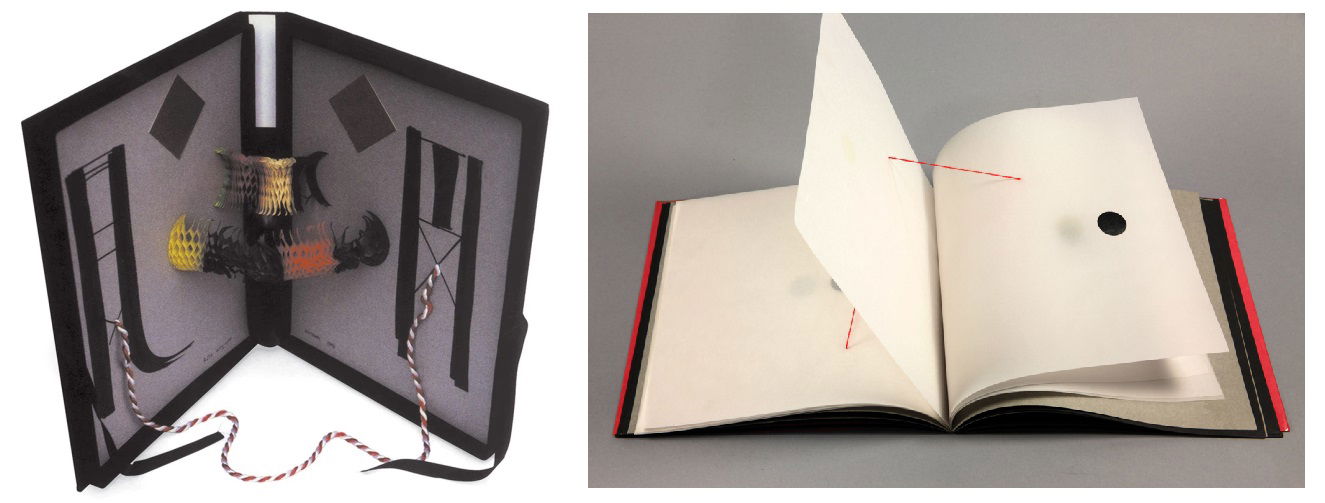

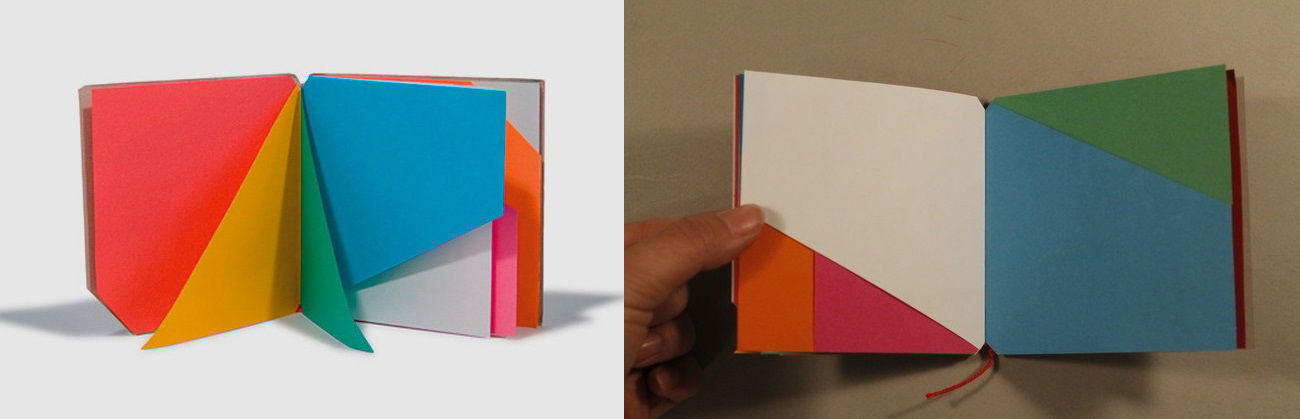

He also understood books as objects and explored this idea intensely through a series called Libri Illeggibili (unreadable books). These works abandoned textual communication in favour of aesthetic, materiality and the physical experience of interaction (e.g. turning pages was about rhythm rather narrative). They are beautiful and fascinating and it is better to show than write about them.

Me and other stuff

I thought I’d end with a list of things I’ve done with books other than read them,

- Use an edge to rule a straight line

- Pile some under my computer monitor to raise its height

- Lean some paper on one when I want to draw in bed

- Press a particularly pretty and meaningful flower between some pages

- Fan myself on a hot day, with a skinny one

- Cut up pages and collage with them

- Cut a secret trench inside and send contraband through the mail (true! It was very exciting)

- Lie in the sun and snooze with one covering my face for shade and darkness

- As a weight to stop towels blowing off my balcony

1Also rainbows are pretty.

2As opposed to the link-following ability of digital – again, neither is better or worse, just different and it’s cool we have both.

3And she was the first woman to train teachers.

4In many ways she completely missed the original intention of Pestalozzi’s method but that is for another day.